Key Points:

- Changes to non-spousal inherited IRA rules could big huge implications for those with such accounts.

- Non-spousal inherited IRAs can no longer be passed down virtually forever.

- Running simulations of taking the distributions in various ways is the best way to find out what's best for your specific situation.

Under the new rules, there's a clock ticking on non-spousal inherited IRAs.

It used to be--and still is, in the case where the original owner of the IRA died before the end of 2019--that owners of traditional IRAs inherited from someone other than the original owner's spouse only had to take annual required minimum distributions. Otherwise, an IRA could be passed on, theoretically, for generations.

It's different now. If the original owner passed away January 1 of this year or later, the assets inherited by the non-spouse need to be depleted (and taxed, as income) within 10 years (with some exceptions).

As before, the beneficiary sets up an inherited IRA account--separate from any other IRA accounts they may have, so as not to comingle the assets. Once that's complete and the assets have been moved over, the beneficiary has to start thinking about how to take the assets.

They have a few options. They could say, "I'll take all of it now, thank you," and be done with it. Unless they're really desperate for the money, though, that's a bad idea, because of the income taxes the move will generate.

The beneficiary could instead just keep an eye on the 10-year clock and take the money at random intervals. A little bit this year, skip next year, a lot a few years later--any combination at all, really, as long as it's all done within 10 years. This method could make sense if the inheritor's regular sources of income are irregular. Perhaps the beneficiary is a gig-economy worker, or an independent contractor who goes through boom-and-bust times. In the boom years, they might minimize or skip the withdrawals from the IRA because they don't need the money and want to keep income taxes as low as possible. In leaner times, they might lean on the IRA a bit more.

Robbing The Future To Pay the Present

There's no reason to withdraw money that you don't really need from an IRA. Yes, you could simply take the money and put it back to work in the stock market in a taxable account. But then you've arguably penalized yourself in multiple ways. You'll have to pay income taxes on income you didn't really need, as we just mentioned. But what could be an even bigger deal is that, in taking the money out of the IRA, you're stealing from your future by removing the possibility of tax-deferred growth in those investments. If you do take the money and invest it in a taxable account, any gains you realize--and you might realize gains whether you want to or not, if you invest in mutual funds--will be taxable. That wouldn't happen if you left the money in the IRA.

Those are two ways to do it. There are two more. The first is waiting until the last possible moment to take the money. This is tax deferral to the extreme, and really the whole point of an IRA. The other is to take a certain portion of the account each year over the ten-year period. You would start with one tenth, then one ninth the next year, then one eighth, and so on until the account is depleted.

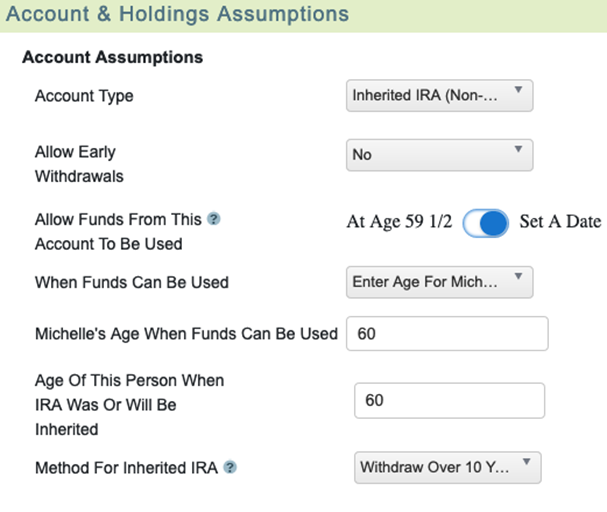

WealthTrace allows you to simulate the distributions from an inherited IRA in a few different ways.WealthTrace allows you to simulate the distributions from an inherited IRA in a few different ways.

WealthTrace allows you to simulate the distributions from an inherited IRA in a few different ways.WealthTrace allows you to simulate the distributions from an inherited IRA in a few different ways.

With these last two options, the benefit of the former is clear: When it comes to taxes, paying them later is always better. The benefit of the latter is that it's a somewhat predictable stream of cash flows, though subject to the whims of the market just as any investment is. We thought it would be useful to simulate both of these methods under different circumstances and see which would be best for a retirement plan.

What's The Best Way?

Let's run through an example using the WealthTrace Planner. A couple in their early 50s believes they will be inheriting an IRA--worth about $500K now--in about eight years. They are trying to determine the best way of drawing down on that money, which will almost surely grow in value between now and then, when the time comes. Leaving out that anticipated inheritance, the couple has around $640,000 in taxable investments in various asset classes. They plan to retire relatively early, in about 10 years.

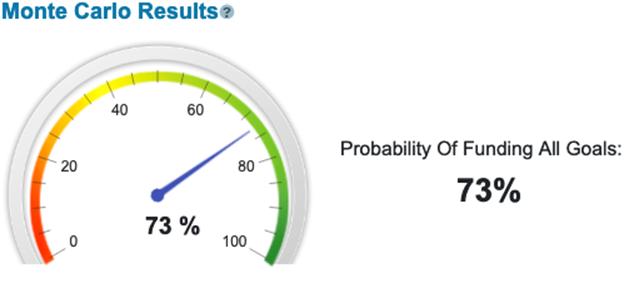

If they take the lump sum option, their plan has a 73% chance of succeeding, according to a Monte Carlo simulation:

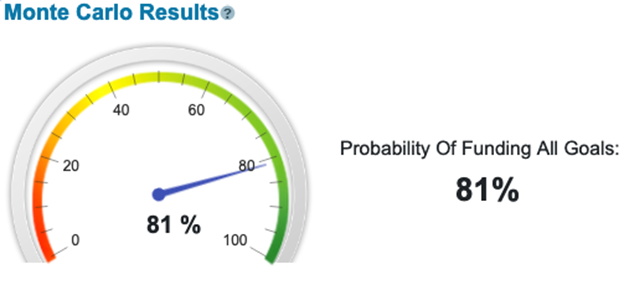

However, if they take the distributions over 10 years, things look a lot better for them:

Results May Vary

So why the big difference? When we added this feature into WealthTrace, we figured taking the lump sum at the end of the period would nearly always be better. But here we are with a situation where that is not the case. If we were to dig into it further, we would probably find that this couple simply needed the money each year over the 10-year period to cover expenses. Without it (or, rather, if they wait to take it all at the last minute), they have some lean years, reducing their plan's probability of success.

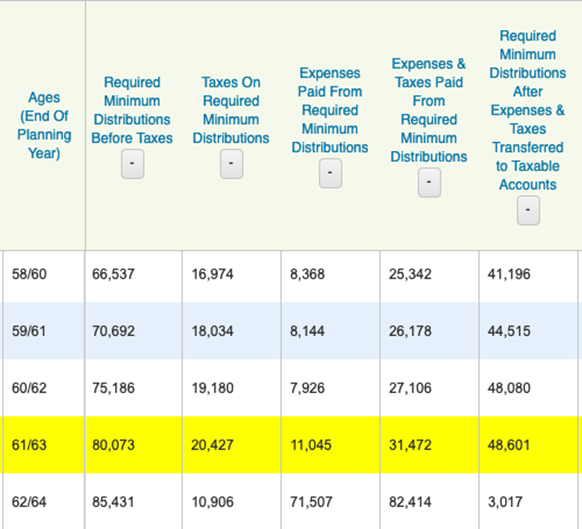

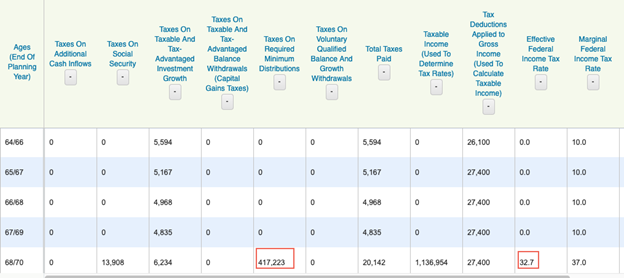

Taking the distributions over the ten-year period (with five of those years shown here) means the funds are available for use to pay living expenses and taxes.

It probably also doesn't help that, under the lump-sum option, the taxes are more than double what they are under the 10-year option. Taxes are deferred, yes, but the distribution is quite large due to compounding of total returns, so the tax rate scales up.

Depending on, well, lots of factors--other sources of income, for example, or one's timeframe--the results will vary. As with so many things investment related, it's best to have a way to run some simulations before making a choice you might regret.

How will your investments and retirement plan hold up under various scenarios? Sign up for a free trial of WealthTrace to find out.